Naples' boxcar benefactor follows a calling to Ukraine refugee camps

Harriet Howard Heithaus

Harriet Howard Heithaus

Jack Nortman has the story of his parents' wedding seared into his personal narrative of family history as if he had been there.

Nazi troops, on the march through Poland for Hitler's September, 1939, blitzkrieg, burst in during their ceremony. Everyone ran, including the bride and groom.

"I don't even know if they got to say, 'I do,'" their son said.

A number of guests who were caught were executed, murdered in cold blood in their small Polish village. The newlyweds escaped to Russia, which could only be marginally termed an escape. Labeled "unreliable elements" in the Soviet Union, Jews, including young Rose and Morris Nortman, were herded into boxcars and shipped off to a Siberian gulag as laborers.

From a Russian gulag, American resolve

Perhaps their stories of that terrifying boxcar ordeal, which brought Nortman to replicate it for visitors to The Holocaust Museum and Cohen Education Center in Naples, has strengthened his determination to personally participate in Ukrainian relief. Perhaps his parents' years surviving in permafrost genetically hardened the steel in the Naples man's resolve to be there in person. Likely both have. Nortman and his sister, Margie Commerford of Minneapolis, are headed to the Poland-Ukraine border to help refugees — as many as they can among the nearly 3 million who have fled the advance of the Russians.

If it means crossing into Ukraine, Nortman is ready, even if it gives his wife a lump in her throat and frustrates the U.S. State Department. It has plastered an Advisory Level 4 on the country: Do Not Travel.

For those who ignore warnings, it lists practical advice, among which is: "Draft a will and designate appropriate insurance beneficiaries and/or power of attorney."

Nortman shrugs off the alarms.

"This thing has taken a really personal toll on me," he admitted. He was born in a displaced persons camp after the Russians released his parents at the end of World War II. The family's transmitted pain of those refugee years is still with him: "My parents, mostly — not me, because I was a baby — went through the exact same thing that's happening now.

"With the exception that no one helped."

Nortman has vowed that he will help. He and Commerford are planning three intense weeks in Poland, at its border with Ukraine and in Warsaw and Krakow refugee camps. Their mission: finding and supporting the most effective organizations that tackle the greatest needs.

But what are they?

A sister sees not aid, but an honor

"Things are very fluid down there. Things change every 24 hours," Nortman conceded of his coming trip. "Something that I was working on three weeks ago today may not be worth anything."

Still, there are needs that keep recurring. Medical equipment. Undergarments. Pocket money.

"They can't use them in the U.S. when they're expired," Nortman explained of the medical items. "But there's nothing wrong with them. So I'm getting a lot of medical equipment that I'm going to be taking to the border," He can use more of it.

"They have a shortage of women's and children's underwear. And bras. They don't advertise that," he said. "I'm not looking for used ones. I'm networking right now to see if I can get the manufacturing companies to give me a couple large boxes to take over." Before this story was even written, he had found a source for bras.

That's Jack, joked his sister: "They say they need socks and he gets the president of the sock company of the whole wide world."

But she is clearly aligned with her big brother on this mission. Commerford said she'll be the sounding board for Jack's ideas in Poland. It is, she says, the best possible inaugural visit to a family homeland she has never seen.

In Minneapolis, Commerford has flexible time as a sales personality on "ShopNBC" for her family's business, just as her brother has in his business as a real estate managing broker. But she doesn't see this as swooping in to save people.

"I'm going there feeling I am privileged to help others who are in that same situation that our family was in long ago," she said.

"We were refugees. I don’t remember anything and Jack remembers very little. But the fact that it's happening again, and happening in that part of the world, makes you feel more connected to it."

This Ukrainian relief is for stability

Nortman has written to family and friends asking them to contribute, as they see fit, to the trip. He is also accepting donations from the public through his Boxcar Foundation. (For those who want to help or contact him, the website is boxcarfoundation.org.)

"They're getting some medicine, some food, even some shelter, but they have no money," Nortman said. Gift cards, to help people with initial housing needs, could leverage some short-term stability.

"Every cent — one hundred percent of every dollar — I'm collecting is going on the ground to the people. Even if we partner with another organization in what we're doing, no organization can take fees," he declared. "(There will be) No organization's administrative reimbursements. I'm very emphatic about it because I want every dollar I collect from my friends, relatives and people in Naples — it goes on the ground."

He's personally paying for all the travel expenditures for the two of them, and even for a nephew, Darrin Commerford, who may come along to document the mission.

That doesn't surprise Susan Suarez, executive director of the Naples holocaust museum.

"He is a very generous philanthropist himself," she said of the former board member. Nortman spent four years searching for, and then paying for restoration of, the authentic 10-ton Holocaust-era railway car that has become a traveling history exhibit for students around Southwest Florida. From that, his Boxcar Foundation was born.

"He's extremely passionate about Holocaust education, and about helping people of all different religions and races and stripes to have respect for each other and tolerance, so this type of atrocity that the Holocaust was never happens to anyone else."

He's also, she added, "very brave" to be undertaking this trip.

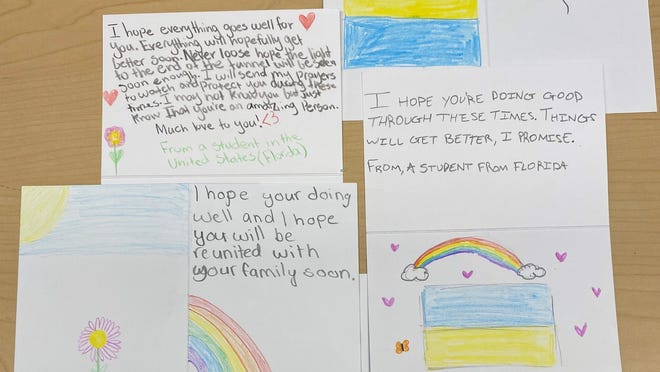

The museum is sending its own Naples contribution. A group of Bonita students were asked if they wanted to send cards to the children of Ukraine, and they responded with zeal.

"Some of them make you smile. Some of them make you cry," Suarez said.

Mission, say volunteers, knows no age

They will go with Nortman, who is working to combine financial efforts with another charity to establish a day camp for refugee children.

"The trauma they get is something that is not, let's say, on the top of the agenda at the moment," he said of the refugee resettlement.

That time at day camp can also give mothers the ability to find part-time jobs. The children's fathers are still fighting in Ukraine, and Nortman knows that charity is deep, but not eternal: "They need money."

Nortman and Commerford may be older than the typical relief organizer. They care about that as much as they care about State Department advisories. Nortman turned 76 on May 3.

"But I'm very immature 76," he said slyly

Commerford, 71, laughs at the idea of age making a difference: "I've got energy to burn."

Harriet Howard Heithaus is arts and entertainment reporter and feature writer for the Naples Daily News/naplesnews.com. Reach her at 239-213-6091.